Federal, state and local regulations

State and local regulations vary by state. As you are using insects as food, follow all of the regulations that govern food production. An overview can be found on the FDA website.

USDA or FDA

On a Federal level, insects used as food fall under FDA oversight. The USDA’s Food and Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) regulates meat, poultry and eggs. Everything else defaults to FDA regulation. FDA regulates sea food (which is most similar to insects …think shrimp and soft shell crab) and even covers game such as venison.

The USDA may be involved in insect farming through their Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) agency. For example, if you want to import a new species that is not currently in the US, you would need to contact APHIS.

No regulations address insects consumed as food in USA

Insects aren’t mention in regulations except in the Food Defect Action Levels. Insects are an unavoidable defect is some agricultural products such as tomatoes. Limits are set as to how much is allowed. However, this context does not apply when insects are purposefully added as a food ingredient.

My recommendation is to use the FDA-Seafood guidance documents for insects to ensure that wholesome food is being produced. The FDA has specific regulations for seafood because they are relatively high risk food products. Lobster, crab and shrimp are regulated by FDA-Seafood.

Grasshoppers are the shrimp of the land.

FDA Seafood Guidance documents link – FDA Seafood

Food safety hazards for insects

As for any food ingredient or product, potential hazards must be evaluated and monitored. The standard process is to use HACCP (Hazard Analysis & Critical Control Points)

Some potential hazards for edible insects:

- Choking Hazard: Arthropods can have long legs that can potentially be a choking hazard. A lot of common foods are choking hazards like hot dogs and popcorn so don’t blow this out of proportion. Bay leaves are a hazard because then can cause splintering and cuts when consumed whole/crushed. Ensure that the particle size is sufficiently small in cricket flour. For whole crickets and grasshoppers, evaluate your supply to on the rigidity and hardness of the exoskeleton. Young cricket exoskeleton is still soft. Most dried crickets fracture and crumble easily and don’t pose a risk.

- Pathogens: Microbiological food safety will be something your company will need to address as you go from start up to and sustainable food business. Its common practice for established food companies to monitor and control yeast, bacteria and fungi. Startups can accept a lot more risk in this area. Companies that purchase cricket flour can leverage their supplier for microbiological information. A baseline measurement is Arobic Plate Count (APC) which indicates the total amount of bacteria present. The logic is that if there are a lot of total bacteria, it is more likely that there will be bad bacteria. For raw crickets, a producer can measure for the presence of pathogens as part of their quality control program. As pathogen testing requires resources, an alternative is to recommend safe handling procedures for raw insects. This is the practice for raw red meat and poultry. More info at Micro Standards Link.

- Environmental Hazards: These are best controlled for via farming. Good feed in will result in good food out. Post-harvest analysis for wild caught can be performed by outside labs such as Certified Laboratories who specialized in doing safety analyses.

- Keep in mind there may be some unforeseen issues such as anti-nutrients, side-effects from high chitin consumption and inherent toxic chemicals.

How can you legally use insects in food?

From the FDA website:

“GRAS” is an acronym for the phrase Generally Recognized As Safe. Under sections 201(s) and 409 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act), any substance that is intentionally added to food is a food additive, that is subject to premarket review and approval by FDA, unless the substance is generally recognized, among qualified experts, as having been adequately shown to be safe under the conditions of its intended use, or unless the use of the substance is otherwise excluded from the definition of a food additive.

The approach to legally sell insects as food is by making a GRAS determination. The legal requirements for making a GRAS determination are quite strict and can be found here http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/

Three approaches businesses can take to make a GRAS determination:

The “common sense” approach: People have been eating insects for the past 10,000 years. 2 billion people around the world currently consume insects as part of their diet. They are already in our food coming from unavoidable defects. Here is a summary of people eating insects without ill effects. Of course they are safe.

The “I have done my homework” approach: We have assessed the safety of using insects as food. The insects are farmed for human consumption and produced using the attached HACCP plan. The product is free from hazards. Here is the most current research on the safety of using insects as food.

The “GRAS determination” approach: This approach is best executed using help from a firm that specializes in GRAS determinations. They use scientific evidence to show that they are safe. The end result is a GRAS dossier the meets the legal requirements for a GRAS determination.

The first two approaches would not pass the scrutiny of FDA review. However, because the edible insect industry is very small and that evidence is lacking showing that insects are harmful, it is unlikely that the FDA will prevent companies from producing entomophagy products.

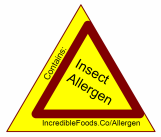

Are insects a food allergen?

Insects are a potential allergen. Insects are very similar to other arthropods and therefore have similar protein. Research to date has not proved that insects are indeed allergens or that they are cross reactive with shellfish allergens. A costly clinical study is required to prove this. It would be interesting to test cricket flour using a shellfish ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) test. While the test would not be definitive it would provide information to help assess the risk from a business standpoint. That being said… insects probably are an allergen even if we can’t prove it. The recommended industry practice is to include an advisory statement such as:

ALLERGY WARNING: Contains Insects (people who are allergic to shellfish may also be allergic to insects)

What do you need to do to protect your company?

Manufacturers that use insects need to have a safety dossier available upon regulatory inspection. Even if it’s not that thorough, something is better than nothing and it shows that you have given it some thought. Follow regulations and best practices that apply to all food products. Include arguments in the dossier that support a GRAS determination. Have documentation and records showing that good, wholesome foods are being produced.

Insects are “new” to our food supply and carry some unknowns about regulation, safety and market growth. It is ultimately a business decision to determine how best to mitigate those risks and grow a new industry.